A few weeks ago Ben Erez wrote a guest post on Lenny’s Newsletter to provide a different perspective from Marty Cagan’s podcast episode where he speaks on many topics including why companies would be better with empowered PM cultures, aka the product operating model, and why feature team PMs are more akin to project managers than product managers. Ben made the case that feature teams are not innately wrong, and that “feature factory” PMs are real PMs doing important work. Ben writes:

At one point, Lenny asked Marty for his response to a LinkedIn post I wrote about why feature factories—businesses that focus on outputs over outcomes—might actually be the optimal product culture for some companies. Marty said that in the long run, this way of thinking leads to building products that nobody likes (e.g. Oracle and SAP). On that point, we’re in agreement. Where our thinking diverges is that I see the feature factory as the right choice for some CEOs to run their companies, especially when those CEOs have a clear and compelling product vision.

While I don’t think that feature factories make for better businesses, I do believe that many founders have a clear vision of what needs to be built in order to win; the resulting environments can often feel like feature factories because product teams are expected to execute on top-down directives. And VCs love to back these types of founders (pattern-matching to Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, etc.).

I read Ben’s post with interest as I am always open to learning something new. There are very few disciplines in which we have complete knowledge and I don’t think product development is one of them. I also believe that often different perspectives are just shades of gray in that there isn’t a right or wrong, just pros and cons that one person values more than someone else does. In technology this certainly seems to be the case to me. So, I thought it would be worthwhile to explore if indeed the feature model is the right choice for CEOs who have a clear and compelling product vision.

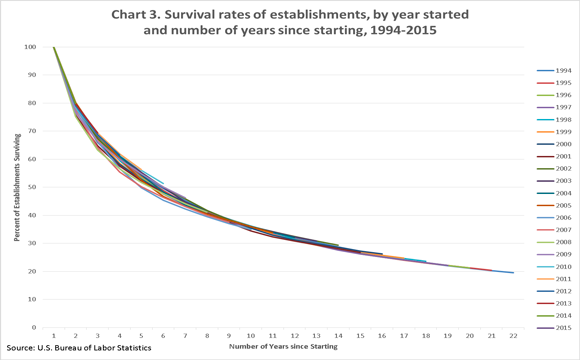

Entrepreneurship plays an important role in the U.S. economy despite the trend of the number of jobs created by startups (establishments less than 1 year old) decreasing from 4.1 million in 1994 to 3 million in 2015. There are a number of possible reasons for this including efficiency gains amongst particular skills as well as a massive increase in outsourcing and automation. In 1994 you probably hired your own accountant soon after you started whereas today that is generally outsourced for many years. What hasn’t changed, however, is the survival rate of startups. According to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, startups have approximately a 33% survival rate in the first 10 years (see chart below) regardless of what year they were started. Note that this data from BLS includes all types of companies including restaurants, plumbers, landscapers, as well as tech startups. Focusing more narrowly on tech startups, according to Failory and their sources, 9 out of 10 startups fail, 7.5 out of 10 venture-backed startups fail, 2 out of 10 new businesses fail in the first year of operations, and only 1% of startups become unicorn firms like Uber, Airbnb, Slack, Stripe, and Docker.

If we switch our lens from the company level failure to the feature level and focus on experiments (A/B tests) of feature changes in technology products, we see a similar trend. A 2017 Harvard Business Review article states, "At Google and Bing, only 10% to 20% of experiments yield positive results. At Microsoft, a third are effective, a third neutral, and a third negative." This is exactly what I’ve experienced, you have about a 15% chance of a first product or feature launch yielding positive results as measured by some customer-related metric like sales, engagement, retention, conversion, etc. According to a post on MIT’s professional education blog, out of the 30,000 products that are launched yearly, 95% fail. When citing these statistics, I like to point out that these are not arbitrary ideas that were thrown out into production. These were well throughout ideas that product managers and product teams deemed likely to be successful enough to spend the time developing them.

So, is it completely coincidental that we have a very high rate of failure in companies, especially tech startups and we have an extremely high level of failure in feature changes and launches? I suspect not. I think the problem is what Marty and Ben agree on, focusing on outputs instead of outcomes, “…leads to building products that nobody likes (e.g. Oracle and SAP).” Whether that is at a feature level or at the company level. In my opinion, a lot of startups fail because they are in fact features and not products. A simple definition of a product vs a feature is, “a product can be described as something that customers consider valuable enough to pay for. It is an item, tool, environment, or even a service for which buyers would be willing to pay. A feature by contrast is a part of a product.” Admittedly, sometimes the difference is hard to tell. Steve Jobs is noted for having said that Dropbox was a feature and not a product.

Where Marty and Ben’s ideas diverge, the data sides with the product operating model being superior to the feature model even for startups with a strong product visionary. Just because a CEO or founder has a “...clear and compelling product vision” doesn’t mean that it is any more likely to be successful. I think this is why we see so many successful startups pivot. A recent study finds that “startups that pivot once or twice raise 2.5x more money, have 3.6x better user growth, and are 52% less likely to scale prematurely than startups that pivot more than 2 times or not at all.”

A recent study found that the most common cause of failure of startups is no need of the product in 42% of the cases. Researchers stated, “the founder of the startup is firmly convinced of the originality and innovativeness of the product and if it comes to production without prior analysis of customer segments, the product may not find the right feedback from consumers. Startup will not help great technology, excellent data on customer buying behaviour, expertise of team members if it does not address the current market need.”

This leads me to the question of why so many people can’t see the problem with coming up with a great idea, spending months or years building it, only to launch it to absolutely no fanfare? I think the reason is that most of us don’t build products and those of us that do, build within one discipline e.g. software, and never see the large number of iterations and pivots that are required to eventually find a great solution that resonates with people. Edison famously failed over 1,000 times before he found the right filament for a lightbulb. WD-40 is named after the 40th attempt to perfect its water displacing formula, as recorded in the lab book of the chemist who developed it. If these stories weren’t popularized, many of us non-chemists would have assumed someone had a great idea, mixed some chemicals together, and launched it to wild success.

Some entrepreneurs get lucky or maybe some of them are just more gifted than others in terms of product visions but it’s really hard to tell the difference and we often misattribute our success to our skills. To me the data clearly shows that ultimately a product team's success is intrinsically tied to the focus on outcomes over outputs. Despite the allure of a top-down, feature-heavy approach for clear-visioned CEOs, statistics and historical trends suggest a reality where the product operating model, which emphasizes outcomes over outputs, yields more sustainable success. This model not only challenges teams to meet immediate goals but also to deliver long-term value, which is essential in the volatile world of startups where the difference between a feature and a viable product can determine the very survival of a company. Thus, entrepreneurs and product leaders must critically assess not just the vision but also the strategic approach to product development, ensuring that they are building something that is a valuable product that truly resonates with users. This balance might not only lead to higher survival rates but could also redefine the trajectories of many startups, steering them toward becoming the next generation of market-defining giants.

So true Mike !

While an interesting perspective, your article paints a picture of visionary entrepreneurs not being connected to actual user needs or solving a real problem. This is a broad, inaccurate generalization that perhaps was more true in the past than it is today. In my experience, today's entrepreneurs have a wealth of resources on how to zero in on real user needs. The fact is than in many cases, those entrepreneurs know the problem better than anyone else in the company, typically having spoken to more users than anyone else.

To assume that a startup entrepreneur will simply handover product direction to someone who, although skilled in product management, has less background and deep user empathy in that problem space, is foolish. This is where the empowered PM model falls flat. Most PMs in such companies who read Cagan or the derivatives become frustrated that they are not fully empowered. This needs to stop. They need to realize that founders will be prescriptive, so they should strive to add product rigour to the founder's directives rather than feeling disempowered.