I’ve thought a lot about two-sided marketplaces since I stumbled into my first one over 20 years ago. Since that time, I’ve worked at a number of them from ad networks to payment platforms to marketplaces for handmade items. I’ve even published papers on social networking sites, which are classic two-sided networks of folks that produce content and those that consume it. I am a huge fan of marketplaces. They are as unique in their dynamics as they are diverse in their application. In trying to organize my thoughts around marketplaces, I’ve come up with six concepts that I think are, if not unique to marketplaces, then certainly important to properly understanding them and thus should be considered when building, growing, or running one.

Let’s first define a marketplace vs an ecommerce retailer or service provider. Merriam-Webster defines marketplaces as “an open square or place in a town where markets or public sales are held.” This definition reminds me of the Aloha Stadium Swap Meet & Marketplace where since 1979 over 400 vendors stakeout space in concentric circles outside of the stadium. Moving this concept into the electronic world, Wikipedia expounds on the concept of a two-sided marketplace as “...an intermediary economic platform having two distinct user groups that provide each other with network benefits. The organization that creates value primarily by enabling direct interactions between two (or more) distinct types of affiliated customers is called a multi-sided platform.” Contrast this with ecommerce which is simply the activity of electronically buying or selling products or online services or over the Internet. Two primary characteristics of marketplaces are 1) that in order to achieve benefits they require economies of scale and 2) they are a manifestation of the benefits of network effects. This is different from ecommerce retailers who may or may not share the benefits of economies of scale with their customers and who do not benefit from network effects. As I mentioned earlier, marketplaces are very diverse ranging from the sale of goods (eBay) to payments (American Express) to professional networks (LinkedIn) to dating (Match). Marketplaces are even differentiated in law. Under Section 230 of Title 47 of the United States Code marketplaces are provided immunity from liability for providers and users of an "interactive computer service" who publish information provided by third-party users. Without this provision, a dating marketplace might be held liable for conversation and behavior of its daters.

Now that we share a common definition of an online marketplace, here are my six factors that are somewhat unique to marketplaces and should be considered by folks building or running one of these - chicken or the egg problem, marketplace flywheel, lightning in a bottle, competitive advantage, pricing, and symbiotic relationship. I’ll run through the first two of these in this article and the next four in next week’s article.

The chicken or the egg problem. You’ll all probably heard of this metaphor that describes situations where it is not clear which of two events should be considered the cause and which should be considered the effect. For two-sided marketplaces you have a classic chicken or the egg problem. You need sellers to provide goods, which they won’t do without buyers, but you also need buyers who won’t shop without goods to purchase. How do you get one without the other? In most marketplaces that I’ve seen, the founders have to play some sort of trick to jumpstart the process. Let’s use eBay as an example. We probably have all heard the cute story that Pierre Omidyar built AuctionWeb, later renamed to eBay, in order for his then girlfriend to sell Pez dispensers. However, in Adam Cohen's 2003 book The Perfect Store, eBay's third employee, PR manager Mary Lou Song, admitted that she had invented the Pez story after the fact, in hopes of attracting media attention. The real story was that Omidyar was selling a broken laser pointer. Media outlets from The Wall Street Journal to The New Yorker have printed this Pez dispenser story as fact. This was in the day when press was sufficient enough to get buyers and sellers on to a platform.

Another, less deceitful two-sided marketplace growth hacks comes from Facebook. Everyone knows that Facebook started at Harvard where Mark Zuckerberg was a student. Instead of opening for everyone immediately it restricted access to only major universities, first expanding to Stanford, Columbia, and Yale. This expansion continued when it opened to all Ivy League and Boston-area schools. This FOMO or false sense of exclusivity is now old hat and doesn’t work as well with consumers. However, at the time it worked to create huge demand for both sides, producers and consumers of content, on Facebook’s marketplace.

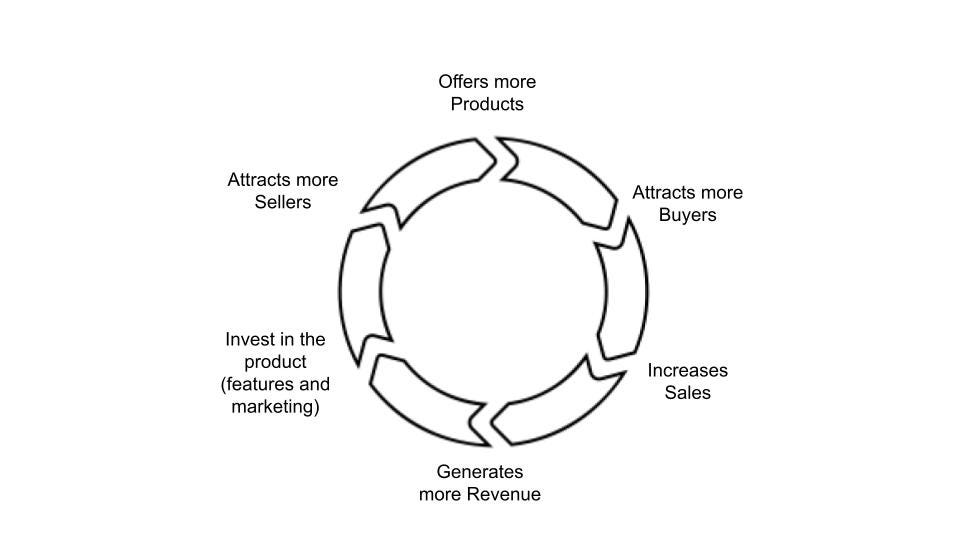

The concept of a flywheel was popularized by Jim Collins in the book Good to Great. On his site he states, “No matter how dramatic the end result, good-to-great transformations never happen in one fell swoop. In building a great company or social sector enterprise, there is no single defining action, no grand program, no one killer innovation, no solitary lucky break, no miracle moment. Rather, the process resembles relentlessly pushing a giant, heavy flywheel, turn upon turn, building momentum until a point of breakthrough, and beyond.” For a marketplace this could not be any more true. As we saw in the chicken or the egg problem, you need one side to build and feed the other side. A typical flywheel for marketplaces might look like this: more products attract more buyers, which increases sales, which generates more revenue, which allows the marketplace to invest more in features and marketing, which attracts more sellers, which offers more products for sale…and so on.

To make things even more interesting, often there are multiple flywheels that interact on a marketplace. One flywheel might focus on how the investment in product engineering drives more sellers because of excellent features for inventory management or easy shipping or low cost payments. Another flywheel might focus on how marketing brings more buyers because of using both brand and performance advertising.

So far we have the chicken or the egg problem that marketplaces need to face in order to get started and we have the flywheel in which a number of things depend on each other and are self-reinforcing. In order to be a successful marketplace you need to get over the inertia of producers not wanting to be on a platform without consumers and vice versa. Some trick or growth hack is often always, in my opinion, needed to get it started. Then you must put your shoulder into the flywheel one turn after another in order to get it up to scale. Miss a step in the flywheel and it slows down or ultimately stops. Each part needs to be constantly monitored to ensure it’s not the weak link. In next week’s article, I’ll cover the remaining four factors that you should pay particular attention to when building or running a marketplace.