Humans are messy. We have emotions and desires, and often we come along with some baggage. Humans are also each seemingly pretty unique. I might like tear-jerker romance movies, vanilla ice cream, and crave fame; whereas you might like slapstick comedies, hot fudge sundaes, and only want to be left alone. The number of combinations that can exist in humans is massive which gives rise to the notion that we are all unique. Besides our mental and emotional traits that make us unique such as our likes, dislikes, and desires, there are many physical characteristics that make us unique. The probability of two people having identical fingerprints is estimated to be around 1 in 64 billion. While we share 99.9% of our DNA with each other, the remaining 0.1% is unique to each individual, except for identical twins. The likelihood of two unrelated individuals having the same DNA profile is about 1 in 10 billion. The probability of two people having the same iris pattern is estimated to be less than 1 in 10^78, making it incredibly unique. Now, I hate to melt my snowflake-centric perspective of humans but at a macro level we are way more similar than any of us probably care to admit.

The human condition encompasses the fundamental aspects and key events of human existence, such as birth, learning, emotions, ambitions, morality, conflict, and death. It suggests that our shared humanity subjects us to similar paths and common challenges. Different religions interpret the human condition differently but they depicted the commonality of human life. Buddhism views life as a continuous cycle of suffering, death, and rebirth, which one can escape through the Noble Eightfold Path. Many Christians believe that humans are inherently sinful and can only achieve salvation in the afterlife through their faith. In the field of psychology, theories like Maslow's hierarchy of needs propose that all humans have similar fundamental needs. Even developmental psychologists view humans, like other animal species, to have a typical life course that consists of successive phases of growth, each of which is characterized by a distinct set of physical, physiological, and behavioral features. The universal patterns and phases of human life are not only evident in individual development but also mirrored in the broader scope of human history.

A famous quip often attributed to Mark Twain is, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” Winston Churchill, in a speech to the British House of Commons in 1948 stated, “Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it,” which was borrowed from George Santayana, who wrote in The Life of Reason in 1905, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” While these contemporary statesmen and authors have provided memorable quotes about the repeatability of human history, they are far from the first to notice this phenomenon. We find a similar sentiment in the Bible’s book of Ecclesiastes, “The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.”

Authors, throughout the years, have been explicit about the repeatability of human behavior, the human condition, and history. Several have even undertaken the topic of the repeatability of all stories ever told. In The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, Christopher Booker explores the concept that all stories fundamentally share common narrative structures. Published in 2004, the book argues that every story ever told can be boiled down to one of seven basic plots: Overcoming the Monster, Rags to Riches, The Quest, Voyage and Return, Comedy, Tragedy, and Rebirth. Booker delves deep into the psychology behind these plots, examining how they reflect human experience and cultural beliefs. He suggests that these plots resonate with psychological archetypes embedded deeply in the human psyche. Spanning examples from classical literature to modern cinema, Booker's work offers a comprehensive analysis of storytelling through the ages, emphasizing the universal themes and moral questions that encourage us to reflect on our own lives and societies.

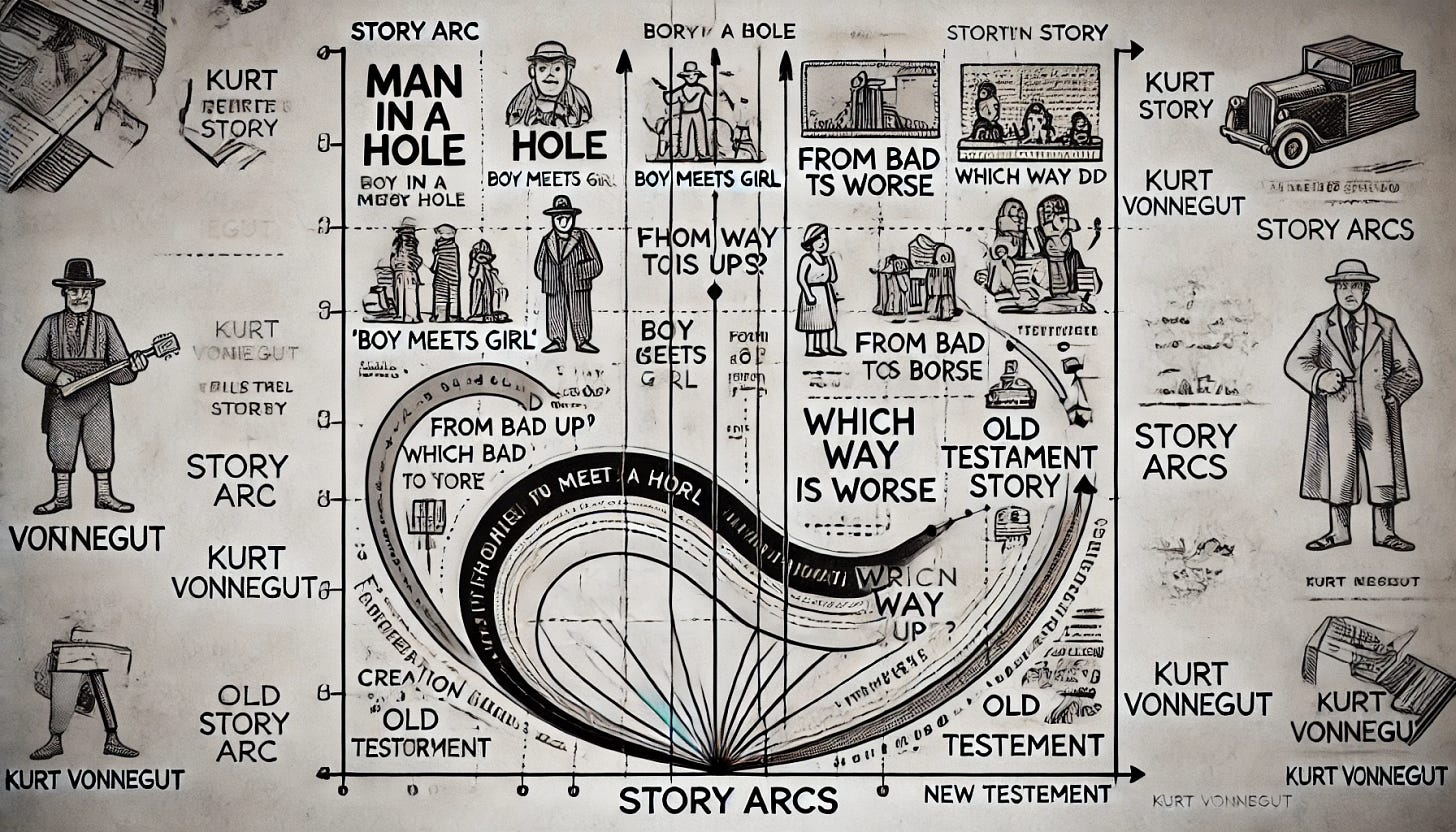

Kurt Vonnegut, in his compelling lecture on the shapes of stories, presents a simple but profound way to visualize the architecture of storytelling. He introduces the idea that stories can be graphed on a chart based on the protagonist's fortune over time, creating distinct shapes that define the narrative’s structure. Vonnegut plots the highs and lows of a story on an axis where the vertical line represents the main character's fortune—good to ill—and the horizontal line represents time. Through his analysis, he identifies several core shapes, including the "Man in a Hole" story, where the character starts off well, encounters trouble which they eventually overcome, and ends better off than at the beginning. Vonnegut’s lecture, infused with his characteristic wit and insight, demonstrates not only how these narrative structures tap into our deepest emotions but more importantly how they are universally recognizable because of their common patterns.

Both Booker and Vonnegut probably were inspired by the much earlier work of Joseph Campbell in his groundbreaking book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, published in 1949. This work delves into the idea of the monomyth, a universal narrative structure that underlies myths from a vast range of cultures. Campbell proposed that heroes, whether Odysseus facing the Cyclops or Luke Skywalker battling Darth Vader, undertake journeys that share fundamental stages. The hero typically receives a call to adventure, a disruption to their ordinary world that beckons them towards a perilous but potentially transformative quest. With the aid of a wise mentor, the hero ventures into a world of trials and tests, facing challenges that force them to develop strength, resourcefulness, and self-knowledge. At the heart of the journey lies the ordeal, a pivotal confrontation with the greatest obstacle or source of fear. Emerging victorious, the hero gains a reward, a treasure or wisdom that holds significance for their world. The return journey is fraught with its own perils, and the hero may face tests that determine whether they can integrate their newfound knowledge into their ordinary life. Ultimately, the hero returns home transformed, forever changed by their adventure, and often bearing gifts or wisdom that benefit their community. Campbell's monomyth, though not a rigid formula, has been a powerful tool for understanding the enduring appeal of myths and heroes, and its influence can be seen in countless works of fiction across various media.

So, while we are all unique beings, the way we develop, think, strive, love, fail, and generally exist is very, very common. The same thing is true in businesses. I learned this by consulting for nearly a decade with over 300 companies. Almost without fail a company would think that their problems were unique, and maybe the details were, but the pattern of the problem was very likely one that we had seen dozens and dozens of times at other companies. Here are five very common problems that businesses face: 1) prioritizing revenue over customer engagement, 2) focusing on the big idea instead of iterating on lots of small ideas first, 3) allowing the brilliant jerk to hurt the team’s performance, 4) focusing on output over outcomes, and 5) trying to measure engineering efficiency instead of worrying about the engineering experience. Let’s walk through each of these.

Prioritizing revenue over customer engagement: Businesses need revenue, and ultimately profits, but neglecting customer engagement in the pursuit of short-term gains is detrimental in the long run. Loyal customers are the backbone of any successful business but you can only push them so far in terms of increasing what they will pay or trying to get more money from them without adding more value to your service or product. Price increase after price increase, without adding more functionality is a dangerous undertaking. When this happens, the focus shifts from enjoyment and loyalty to something that is simply transactional and as soon as a cheaper alternative appears, customers are going to jump. The reason this can be so tempting is that a major scorecard for companies is the profit & loss or income statement rather than engagement metrics. When engagement metrics are included in their quarterly reports, often they are vanity metrics instead of ones that show true engagement. The fix to this is to invest in determining a set of core metrics that measure true engagement of your customers, possibly DAU/MAU ratio, where DAU is the number of unique users who engage with your product in a one day window. MAU is the number of unique users who engage with your product over a period of time, usually a 30-day window. This ratio measures the stickiness of your product – that is, how often people engage with your product.

Big ideas over incremental improvements: The allure of a groundbreaking, industry-disrupting concept is undeniable; however, an overemphasis on grand ideas often overshadows the power of incremental improvements. Businesses that prioritize meticulously testing and refining smaller ideas are more likely to achieve sustained success. Embracing a culture of experimentation is crucial for fostering innovation and adaptability. This approach involves allocating resources for testing smaller, well-defined ideas and utilizing A/B testing to compare different versions of features. Gathering and analyzing user data helps determine the most effective approaches, allowing businesses to make informed decisions.

Adopting a "fail fast, learn faster" mentality encourages a proactive attitude towards failure, viewing it as a valuable learning opportunity rather than a setback. This mindset empowers teams to abandon ideas that don't resonate with the target audience swiftly and without fear, thereby avoiding wasted resources and effort.

By continuously iterating and improving, businesses can develop products or services that genuinely meet customer needs. This ongoing process of refinement not only enhances the user experience but also builds a solid foundation for long-term growth and relevance in the market. Furthermore, a commitment to small, consistent enhancements can lead to significant cumulative gains over time, ultimately contributing to a robust competitive advantage. In a rapidly evolving business landscape, this strategy ensures that companies remain agile, responsive, and aligned with the ever-changing demands of their customers.

Brilliant jerks over great team performance: Talented but toxic individuals can be a double-edged sword. Their brilliance might contribute significantly, but at the cost of team morale and overall performance. A brilliant jerk fosters a hostile work environment, leading to decreased productivity, high employee turnover, and ultimately hinders innovation. Imagine a marketing team where a single, highly successful employee constantly belittles and undermines their colleagues. This not only creates a tense atmosphere but also discourages collaboration and creative thinking. Prioritize company culture and team dynamics. Develop and enforce clear policies regarding respectful conduct. Implement anonymous feedback mechanisms to identify problematic behavior. Address issues constructively and be prepared to part ways with individuals who consistently disrupt team harmony. Invest in fostering a collaborative environment where all voices are heard and valued. A strong team dynamic will not only improve employee well-being but also unleash the collective creative potential of your workforce.

Output Over Outcomes: Busyness doesn't equate to effectiveness and even delivering a project on time and on budget doesn’t guarantee that customers will engage with it or love it. Business leaders often fall into the trap of focusing on churning out deliverables without considering the actual impact on the customer. Marty Cagan explains the pitfalls of this well in his latest book Transformed, the focus should shift from mere outputs to meaningful outcomes. In a recent article Cagan states, “In feature team organizations focused on output, the product teams are there to deliver what the stakeholders prioritize as important. And with so many stakeholders with so many requests, it’s not unusual for product teams to struggle with prioritization. But in the product model, the product leaders have the responsibility to look holistically across the business, and identify the most critical problems to solve, and outcomes to achieve.”

In line with the Product Operating Model, it's essential to empower teams to align their goals with the company’s overall objectives. This involves developing key performance indicators (KPIs) that track the impact of their efforts. Empowered teams are given the autonomy to solve problems and deliver real value, rather than just following a set of instructions. By focusing on outcomes, teams can ensure that their efforts are directed towards achieving meaningful results. This approach not only fosters innovation and creativity but also ensures that resources are used efficiently, ultimately leading to the development of products and services that truly meet customer needs and drive business success.

Focusing on Engineering Efficiency Instead of Experience: Measuring engineering efficiency is very difficult and fraught with problems. This is not from lack of trying over the decades. As an industry, we have tried KLOC, story points, commits, etc. and all have pitfalls. KLOC is lines of code (thousands) and doesn’t measure quality or functionality. Counting commits can misrepresent productivity, as frequent small commits might not equate to meaningful progress. The problems are endless. What we do know is that the overall developer experience or DevEx is really important. As Idan Gazit, senior director of research at GitHub states, “Building software is like having a giant house of cards in our brains...Tiny distractions can knock it over in an instant. DevEx is ultimately about how we contend with that house of cards.”

Red Hat underscores the critical role of DevEx in bridging the gap between various silos within an organization. Improving developer experience involves enhancing communication, providing better tools, and fostering a collaborative environment. This leads to increased agility, reduced burnout, and improved overall productivity, which are crucial for the long-term success of software development projects.

Research indicates that a positive developer experience and high developer happiness are strongly correlated with greater productivity and higher quality outputs. Studies have shown that developers who feel satisfied and valued in their work environments are more likely to be engaged, motivated, and productive. A study from the University of Warwick found that happiness can increase productivity by 12%, illustrating the substantial impact of emotional well-being on work output. Companies that prioritize developer experience often see reduced turnover rates, maintaining team cohesion and preserving institutional knowledge, further enhancing productivity and quality.

The human condition is a fascinating paradox. We are each unique individuals with our own quirks and preferences, yet we share a remarkable number of commonalities. This is just as true in business. Businesses, like people, can be steeped in the belief that their problems are one-of-a-kind. However, I've found that challenges often boil down to a handful of recurring themes. Prioritizing short-term gains over customer loyalty, neglecting the power of iteration in favor of grand ideas, tolerating disruptive egos over fostering a strong team culture, focusing on output over meaningful outcomes, and getting lost in the weeds of engineering efficiency – these are problems that plague businesses across industries, maturity, and size.

The key to overcoming these hurdles lies in recognizing the patterns. By acknowledging that common pitfalls exist, businesses can learn from the experiences of others and implement proven solutions. Just as understanding the universality of the human experience fosters empathy and connection, recognizing the repeatability of business problems empowers companies to learn from one another and navigate the path to success together.