In December 1941, the American people were deeply divided about entering World War II. Isolationist sentiment ran high; most wanted to stay out of the growing conflict overseas. Then came the attack on Pearl Harbor. In his address to Congress the next day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt didn’t bombard the nation with facts or figures. Instead, he told a story. He began his famous speech with the words, “Yesterday, December 7, 1941, a date which will live in infamy…” In just a few sentences, he painted a vivid picture of the day’s events, invoking shared outrage and sorrow. He described the "deliberate" and "premeditated" nature of the attack, casting the United States as the righteous victim of an unprovoked assault. His story wasn’t just about ships and bombs; it was about the American people, their dignity, and their resolve.

The power of Roosevelt’s story lay not in its length or its intricate plot, but in its ability to make millions feel part of something larger. This is the power of storytelling. A friend of mine, who mentors tech leaders and often does so through sharing personal anecdotes, was recently asked, "Where do you get your stories from?" and "How do you know when to tell a story?" This pulled him up short as storytelling comes naturally to him so he hasn’t had to think a lot about it. When he mentioned this to me I was intrigued. Storytelling is a large part of why I write, besides helping to clarify my thoughts, it helps me get better at telling stories. This week I want to explore how and when we tell stories, in the spirit of helping us all get a little better at this very important leadership skill.

How to tell stories

Storytelling is innate in humans. Storytelling may have provided an evolutionary advantage by enhancing survival through effective communication and social bonding. This according to Sanjay K. Nigam, Professor of Pediatrics at UCSD, suggests a neuroanatomical basis for storytelling abilities, potentially reflected in the brain's neural circuitry. Kara Rooney, in her book The Narrative (R)evolution, states, “Storytelling is one of the most innate expressions of human nature. It is also the means by which we store, retain and invent our collective and personal histories.”

Given the importance of storytelling to our evolutionary history, it should be no surprise that there is no lack of suggestions and instructions on how to tell a great story. A quick aside: the use of the word “tell” is a bit misleading as what I really mean is how to create, craft, and develop a story. The actual delivery is a whole other matter since you can “tell” a story via a presentation, in a one-on-one, or even in a newsletter.

A quick Google search provides nearly unlimited options for how to get better at storytelling. There is a Masterclass on how to tell effective stories that include suggestions such as: choose a clear central message, embrace conflict, and have a clear structure. If you are a fan of The Moth (and who isn’t?) you might seek advice from the executive producer, Sarah Austin Jenness’ book How to Tell a Story in which the authors provide advice such as: 1) understand that a story is more than a scene or an anecdote - does the story you want to tell have a beginning, a middle and an end? and 2) develop your story - once you find the story you want to tell, put it under a magnifying glass to blow it up big. Another school of thought on storytelling is the five Cs, which are: Character, Context, Conflict, Climax and Closure. Kelly Parker, in her TEDxBalchStreet talk in 2022 outlines a four-step process to effective storytelling:

Understand the Audience: Identify their current struggles and aspirations to ensure the story resonates

Create Vivid Imagery: Use specific details, characters, and emotions to make the story memorable and relatable.

Propose Thoughtfully: Build trust and credibility before making an ask to align with the audience’s readiness.

Ask Confidently: Present the proposal boldly, ensuring it feels like the natural next step.

The South Park creators, Trey Parker and Matt Stone, gave a lecture at NYU where they explain that between each statement in a story should be a “therefore” or “but” but not a “...and then.” For example, if your story goes “this happens” and then “this happens” and then…well that’s really boring. How Parker and Stone believe an interesting story should flow is more like “this happens” therefore “this happens” but “this happens.”

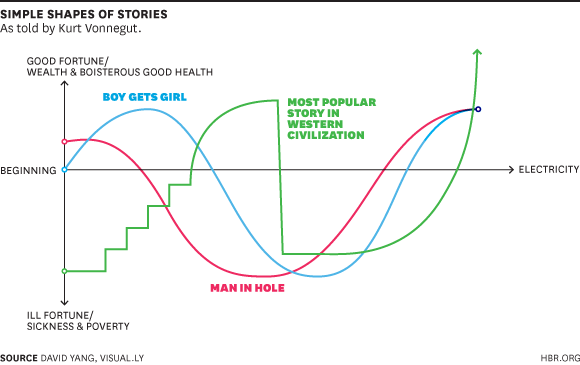

Kurt Vonnegut, in his compelling lecture on the shapes of stories, presents a simple but profound way to visualize the architecture of storytelling. He introduces the idea that stories can be graphed on a chart based on the protagonist's fortune over time, creating distinct shapes that define the narrative’s structure. Vonnegut plots the highs and lows of a story on an axis where the vertical line represents the main character's fortune – good to ill – and the horizontal line represents time.

Ernest Hemmingway is often associated with a story involving a bet with some other authors about who could write the shortest story. Supposedly he wrote “For sale: baby shoes, never worn" and won the bet. This probably never happened and was likely borrowed from a 1917 article in The Editor magazine by William R. Kane about a woman who lost her child, with the title “Little Shoes, Never Worn”. But, as Mark Twain said, “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story” so whatever the origin, the point is that stories don’t have to be long or complicated.

The advice on storytelling ranges from a multi-step process full of details and thought provoking questions to a six word sentence as demonstration of how your mind can fill in the gaps in most stories. So how do we, as practicing raconteurs, know how to tell a story? What do stories need? Being someone known for their brevity, it will come as no surprise that I think stories don’t need to be complicated or long.

A story simply needs a character, a challenge, and a narration of how they overcome (fairytale) or don’t overcome (tragedy). In a business scenario, the character can be your company, the challenge – a competitive threat, with the narration being how you are going to slay that proverbial dragon and be the victor. At its core, every story is about transformation, a shift from one state to another, brought about by the character's engagement with the challenge. In a business scenario, the character might be your company, your team, or even your customer. The challenge could take many forms: a competitive threat, an emerging market disruption, or an internal struggle to adapt to change. The narration is where the magic happens, it’s the process of showing how the character faces the challenge, learns, evolves, and ultimately triumphs or fails.

The key to crafting such a story lies in how the challenge is framed and the resolution is presented. The challenge needs to feel real, relatable, and significant, while the resolution must provide a satisfying arc, whether it ends in victory or serves as a cautionary tale. For example, in storytelling about innovation, the dragon you’re slaying might be inefficiency, outdated practices, or missed opportunities. The resolution shows how your company adapts and evolves, painting a clear picture of the transformation and its impact.

Great business stories don’t have to be long or elaborate. They need to be focused, relatable, and emotionally engaging. The character, challenge, and resolution should align with the audience’s experiences and aspirations, so they see themselves in the journey. Whether it’s about surviving a competitive storm or breaking into a new market, the goal is the same: to connect on a human level and make the story memorable and compelling.

When to tell stories

So, once you have crafted a great, memorable story, when do you tell it? The timing and context of storytelling can often be as critical as the story itself. A story told at the wrong moment can fall flat or feel irrelevant, while a story delivered at the right time can inspire action, build trust, or clarify complex ideas. The art of storytelling isn’t just about crafting narratives, it’s about recognizing the moments that call for them. There are probably many appropriate times for great stories but the ones that seem most important to me are when you want to: connect, make ideas stick, rally people, and celebrate.

One key moment to tell a story is when you need to create a connection. This could be during a team meeting when morale is low, and a story about overcoming adversity reminds everyone of their shared purpose. When faced with a difficult issue or bold idea, sharing a story that resonates with the emotions or fears behind the statement, like a struggle with limited resources or a leap of innovation, can transform a potentially glib acknowledgment into a powerful moment of genuine connection. It could happen in a one-on-one conversation, where sharing a personal anecdote breaks down barriers and builds rapport. Stories excel in these moments because they go beyond facts and logic to engage emotions and foster a sense of belonging.

Another prime opportunity for storytelling is when you need to make an idea stick. Stories are particularly effective in presentations or pitches where complex data or dry concepts can overwhelm or disengage an audience. A well-placed story serves as an anchor, helping the audience understand and remember the core message. Think about the last great TED Talk you watched, it’s likely you recall the speaker’s central idea through the story they shared, not through their charts or graphs. Similarly, naming an idea can evoke a sense of story and connection, making it more memorable and engaging. For example, a data warehouse at a healthcare company was named "Carehouse," immediately sparking a narrative around its role in supporting patient care.

Stories are also essential during times of change or uncertainty. When leading through a transformation or navigating a crisis, stories help people make sense of the shift. They can illustrate why the change is necessary and what success could look like, creating a vision of a better future. For example, when Howard Schultz returned to Starbucks during a time of declining performance, he used stories about the company’s origins to re-inspire his team and reignite their passion for quality and customer service.

Lastly, stories are powerful tools for celebration and reflection. Sharing a story of a team’s hard-won victory during a quarterly review, or recounting a customer’s success as a result of your product, reinforces positive behaviors and builds momentum. These moments give context to achievements, helping everyone understand the journey that led to the result.

Ultimately, the best time to tell a story is when it enhances the human connection. Stories aren’t just fillers or decorations, they’re bridges between ideas and action, between individuals and shared purpose. Knowing when to tell them requires listening, empathy, and an awareness of the situation. A great story, told at the right moment, can move people in ways no spreadsheet or bullet point ever could.

Conclusion

Stories are part of the human condition. They are the threads that weave meaning into the fabric of our lives. They connect us to one another, clarify complex ideas, and inspire action in ways no raw data ever can. As leaders, mentors, or teammates, the ability to craft and share stories is one of the most powerful tools at our disposal. It’s not just about the words we choose but the moments we choose to share them, moments when they resonate most deeply and spark understanding or inspiration. Whether you’re rallying a team, celebrating a victory, or simply breaking the ice, stories have the potential to transform interactions into shared experiences. So, tell your stories boldly, tell them thoughtfully, and above all, tell them often. You may be surprised at the bridges they build and the change they create.