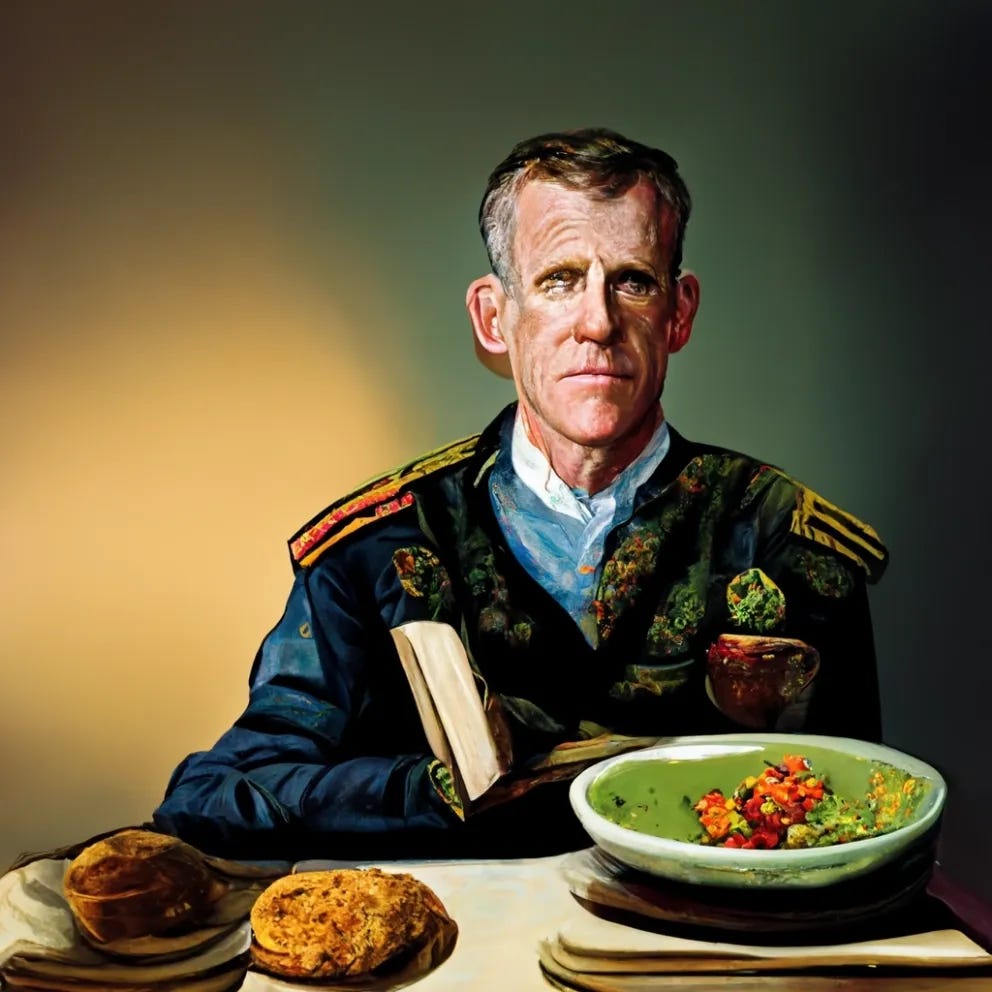

A few weeks ago, I wrote about untrue origin stories, where people make up accomplishments to protect their egos, justify their positions, or put others down. There is obviously a lot of downside of resume stuffing or making up accomplishments, but sometimes leaders gain mythological status whether they want it or it being justified. General Stanley McChrystal, in an interview by Shane Parrish of The Knowledge Project Podcast, talks about his one meal a day practice and how it became a two edged sword. For his personal staff, they referred to it as the “pain train” because during the other meal periods McChrystal wouldn’t stop to ensure they went to breakfast or lunch. But outside of that small group there was this mythology that grew up around it that McChrystal was some kind of Zen warrior who never slept and only ate once a week. Of course those things weren’t true but of them McChrystal says, “the reality is that those things which made the people that worked with me intrigued and in some cases inspired by my commitment were helpful. And, most leaders have some combination of those things that help them be a little bit more effective in leading people.”

In some part of our psyche, we want our leaders to be bigger than life, demi-gods of sorts - heroes. For someone to be worthy of our followership, we need them to be exceptional. This exceptionality can take a number of forms including their primary skill such as management or warfighting in General McChrystal’s case but it can also extend beyond that to include physical or mental feats beyond what most of us can accomplish. In many ways these leaders are modern day heroes. Scottish essayist, Thomas Carlyle wrote in 1841 in his book On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History, “no nobler or blessed feeling dwells in man’s heart” than the feeling of hero worship and that every man “is himself made higher by doing reverence to what is really above him.”

A central part of the hero leader is the hero story, otherwise known as the hero’s journey or monomyth. Joseph Campbell was an American writer and professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence College who’s best-known work was his 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, in which he proposed his theory of the journey of the archetypal hero. Although widely criticized, Campbell’s theory does lay out seventeen stages of the hero’s journey. Researchers at the University of Richmond, Scott Allison and Jennifer Cecilione, state in their chapter of Leadership paradoxes:

Highly effective leaders know that framing their lives and their careers in the context of a good hero story will bring them greater success. Leaders develop personal narratives and use hero characteristics to convey a powerful message that will move followers emotionally and behaviourally (Gardner, 1995; Sternberg, 2011). To maximize the effectiveness of the message, the hero of the story should acquire and retain as many traits that are prototypical of heroism as possible. Ideally, the leader has (1) undertaken some type of risky journey; (2) made significant self-sacrifices along the way; (3) discovered something important about himself or herself and the world; (4) undergone a momentous personal transformation; (5) developed a deep, altruistic desire to share the gift of this discovery with the world; and (6) as a result of the journey, acquired heroic traits such as strength, courage, wisdom, resilience, loyalty, and generosity.

An interesting departure from this mythological hero-leader is the concept of “Superleadership.” In a 1991 paper by Charles Manz and Henry Sims, Jr. in the journal Organizational Dynamics, they introduce the concept that the most appropriate leader is one who can lead others to lead themselves and they state, “Our viewpoint represents a departure from the dominant and, we think, incomplete view of leadership. Our position is that true leadership comes mainly from within a person, not from outside. At its best, external leadership provides a spark and supports the flame of the true inner leadership that dwells within each person.”

My perspective on this is that there is room for both of these concepts in leadership. It’s hard to argue that we still look to charismatic leaders who have achieved some mythical status such as General McChrystal. We also still love a good hero journey - someone called to adventure, refusal at first, finding a mentor, being tested, apotheosis, return with specialized knowledge. There is also space in leadership for the quiet leader who exerts influence to find the best in all of us.

I think it is included here:

https://fs.blog/knowledge-project-podcast/roger-martin/

I'm curious how the concept of a Level 5 leader fits into these archetypes. In that concept, popularized by Jim Collins, effective leaders focus more on what is best for the company than on their hero journey and cult of personality. It is almost the polar opposite of the hero leader driving progress through their strength of will and heroics.

What do you see in these concepts as important to existing and aspiring leaders?