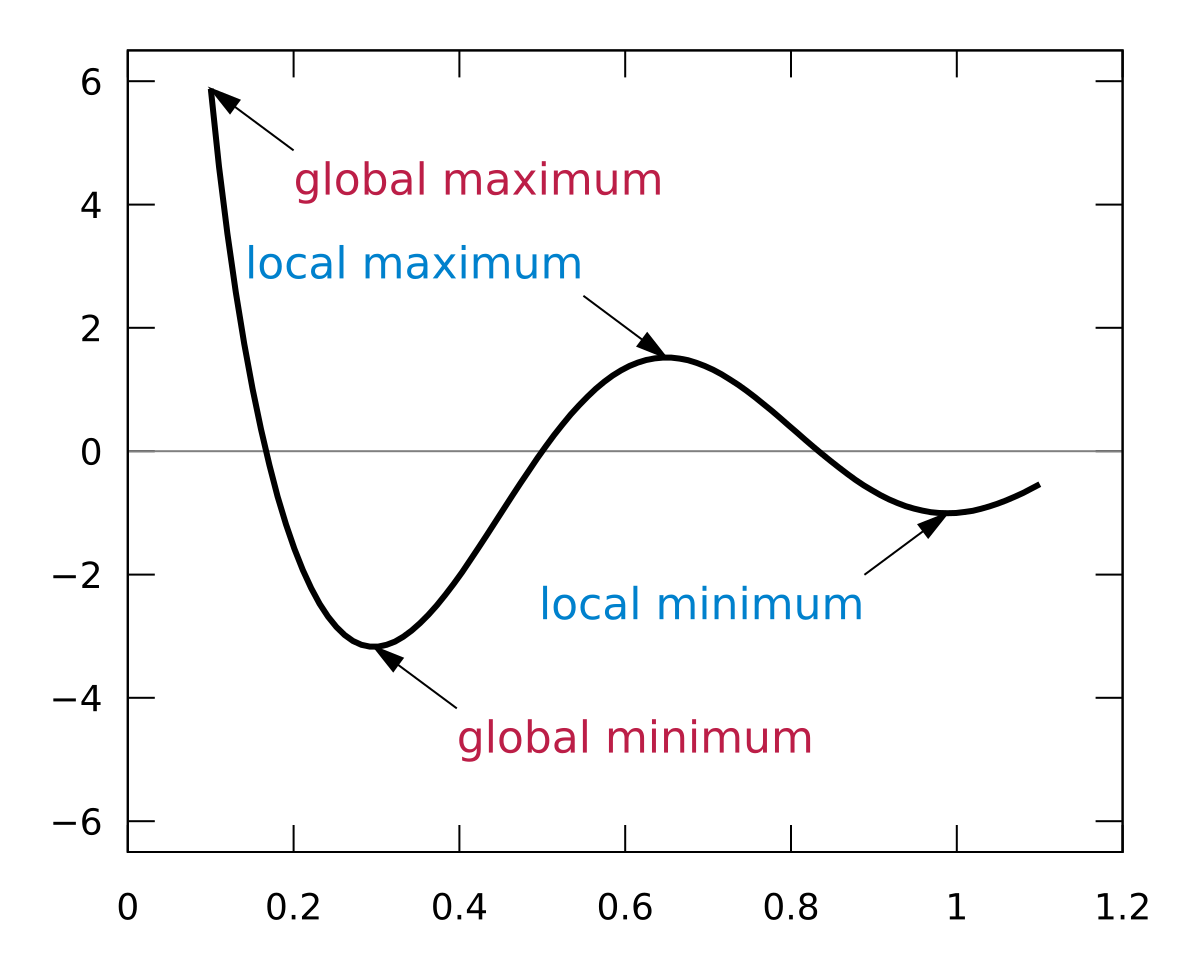

Local Minima

How to avoid optimizing the wrong things

In the context of search algorithms, particularly in optimization problems, a local minimum or maximum refers to a solution or state that is better than all its immediate neighbors, but not necessarily the best possible solution overall (the global minimum or maximum). Many local search algorithms, like hill climbing, are prone to getting trapped in these local min/max. They explore the immediate neighborhood and move towards better solutions, but once they reach a local minimum or maximum, there are no further improvements in the immediate vicinity, so the algorithm terminates.

I was thinking about this problem in the context of business while sitting on an airplane waiting for our already delayed flight to take off. It was a short one hour flight that was originally delayed because of the air traffic control issues in Newark. Once we had received our clearance to take off, we were delayed again because the plane now didn’t have enough fuel to make the short trip. Now, if you don’t know, airlines only put enough fuel in planes to make the trip itself, fuel to reach a diversion alternate airport if the destination is unavailable, and a mandatory final reserve of fuel for emergencies. The reason for this is that the fuel itself is heavy (~6.8lbs per gallon) and every ounce of weight on a plane requires that much more fuel to fly it. Therefore, the more fuel on a plane, the more fuel required by that plane to fly it. Obviously, it saves money and probably some impact on the environment to put in just the right amount of fuel.

The problem as you can probably see already is that the optimal amount of fuel can be hard to predict because of the uncertainty of external factors like weather or air traffic controllers. If you run low, the pilot and flight operations have to coordinate to load more. If you run high, the flights waste more fuel and cost more. The downside of putting too little fuel in is suffered by the passengers mostly, because they are the ones delayed whereas most other costs (pilots, ground crew, etc.) are already being paid whether the flight takes off or not. The downside of putting in too much fuel is suffered by the airline as the flights cost more per leg due to the extra weight.

Now, we all make this same tradeoff, whether we know it or not, when we fill up our ICE cars with gasoline or diesel. If we fill up the tank, the extra weight uses more fuel to haul the extra gallons around. If we don’t fill up the tank, we run the chance of needing to stop frequently and possibly when we are running short of time. Certainly there is a large difference between planes and cars in terms of how much fuel is used but the principles are the same. The US Dept of Energy states an extra 100lbs in a vehicle drops fuel efficiency by around 2%. If your car gets 35 mpg average, a 2% decrease would mean only losing 0.7 mpg. Over the course of a year if you drove 12,000 miles per year at 35 mpg you use approximately 343 gallons of gas, while at 34.3 mpg you use approximately 350 gallons of gas. Thus the 0.7 mpg difference would cost you an extra 7 gallons of gas per year.

Back to my delayed flight. After an already long delay due to air traffic control issues, another delay to refuel was not received well by the passengers. Many of them could be heard audibly groaning and complaining. I have to believe that particular airline lost at least one customer that day.

I’m going to guess that the team responsible for ensuring the most efficient cost per flight is not the same team that is responsible for customer retention. Here we likely have a classic case of a team optimizing for their performance metrics but not thinking about other team’s metrics or even how their accomplishment might impact the overall business. Is there anyone at that airline thinking or calculating how much it would cost to add some amount of extra fuel at the cost to the airline but at the benefit of the passengers? I dare say that there are a lot of folks thinking about local maximums (their team’s goals) but no one is in a position to think holistically about the global maximum (how the overall business performs) except for a very few executives who aren’t close enough to these decisions to influence them.

This is the trap of local minima in business. Teams, like our airline’s fuel planners, optimize for their own scorecard without realizing that their improvements may actually degrade the company’s overall performance. It feels rational in the moment — lower fuel costs, higher efficiency, better numbers in the quarterly report — but the “win” is local. Passengers waiting on a tarmac don’t experience efficiency; they experience frustration. And frustrated customers don’t return.

The same thing happens across industries. Ad teams optimize for revenue per session while user engagement quietly erodes. Operations pushes for leaner inventory while sales teams struggle to meet demand spikes. Finance drives cost cutting while engineering falls behind on innovation. Each group can show its metrics trending in the right direction, yet the company as a whole slips into a worse equilibrium — a local minimum disguised as success.

The antidote isn’t to stop measuring or optimizing, but to recognize the danger of single-variable focus. Just as a pilot balances altitude, speed, and fuel, businesses need counterbalancing metrics that keep one team’s optimization from harming another’s. On-time departures should matter as much as fuel efficiency. Retention should weigh against acquisition. Customer experience should temper raw revenue growth. Without these balancing forces, local improvements masquerade as progress while the business drifts off course.

This is where leadership has to step in. Only those with a cross-silo view can escape the gravity of local minima. But it’s not enough to simply “be aware.” Leaders must actively create the connective tissue between functions, ensuring that efficiency in one part of the system doesn’t translate into fragility in another. In other words, someone needs to own the global maximum, not just applaud a collection of local wins.

So the real question becomes: in your company, who is looking out for the global maximum? If the answer is “nobody,” then you might already be sitting on the runway, engines humming, passengers sighing, and the competition quietly flying overhead.

In engineering - cross-functional teams, DevOps echo the same observations.

- QA teams assessed for bugs caught -> quality is not built in

- Project / Release managers: Release coordination needed, coupling needed -> No incentive to optimise for flow

- Dev story points: writing code and features without thinking about bets and costs as a business and effects for other functions (ops, finance, recruiting, etc...)

- Recruitment: Number of conversions or rate of recruitment can apply pressure on fitness

- UX: designing for "experience" or "edge cases" without factoring costs and upside

Jeff Bezos articulated similar concerns with measuring the wrong thing in his “skeptical view of proxies”.