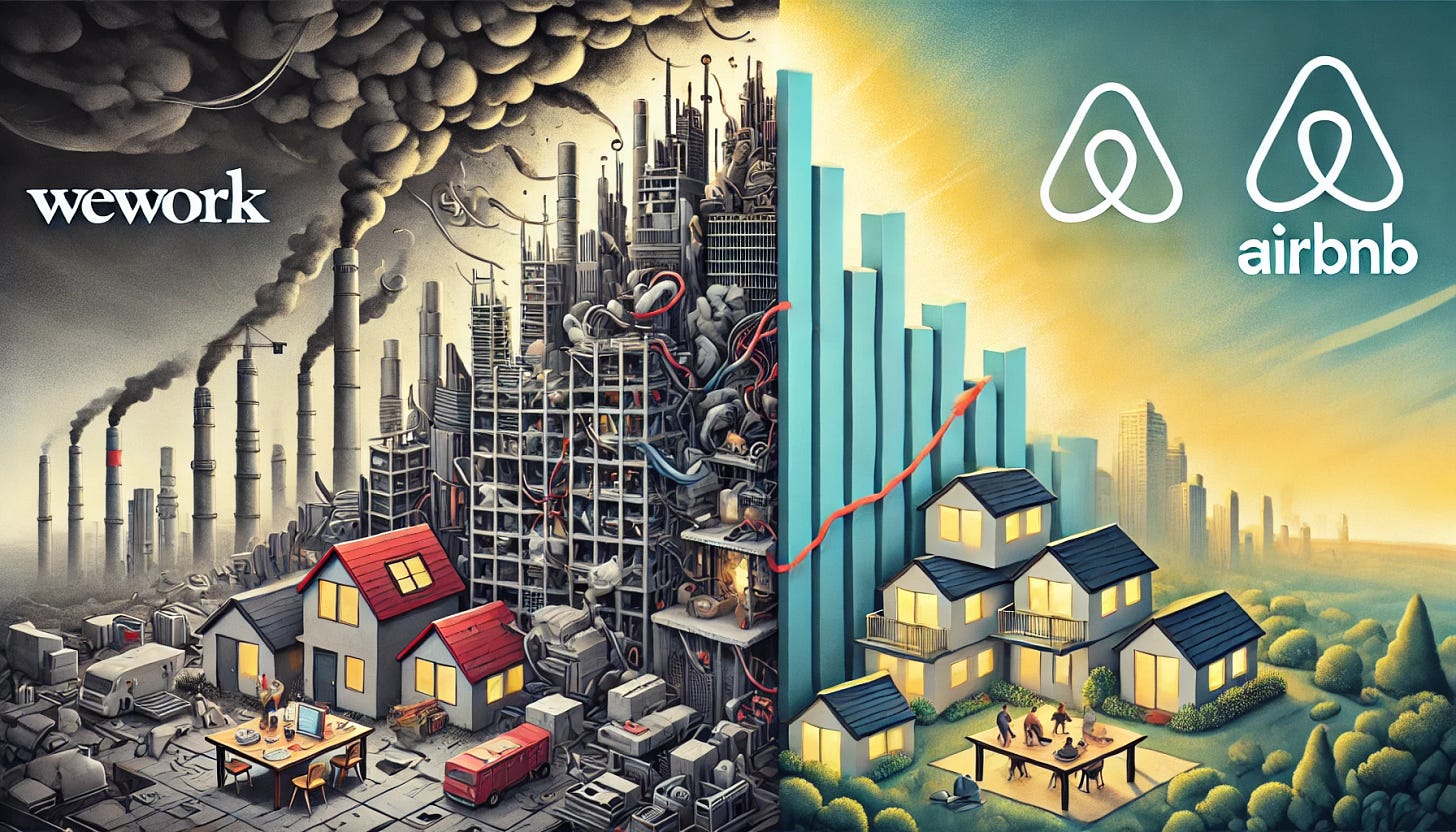

This is the story of two companies, both founded on the promise of transforming how we think about space. One aimed to redefine the way people work. The other, the way they travel. Both rose to fame at roughly the same time, but their paths could not have been more different.

WeWork started with a vision, to create a world where office space was flexible, open, and community-driven. Its founder, Adam Neumann, exuded a kind of messianic zeal, captivating investors with tales of a new era in how humans would work and connect. And to make this dream real, WeWork leased office spaces across the globe by the dozens, sometimes before it was clear anyone wanted them. Between June and September 2019 alone, it opened nearly 100 new offices, pushing its total to 625 locations. But there was a problem. Those shiny new offices weren’t just expensive, they were also locked into long-term leases, often for decades. The plan was simple, to grow so fast that it outpaced the debt. What wasn’t simple was pulling it off.

By late 2019, cracks in the grand vision were impossible to ignore. WeWork’s losses in the third quarter alone more than doubled to $1.3 billion. Every dollar in sales came with more than two dollars in costs. The company tried to launch an IPO, hoping to raise billions to fund this runaway train, but the market balked. Investors weren’t buying the hype anymore. Neumann was ousted, and SoftBank, its largest backer, had to bail out the company. From its early valuation of $47 billion, WeWork’s worth plummeted to less than $8 billion. The world of work remained unchanged, and Neumann’s empire became a cautionary tale about chasing growth without regard for sustainability.

Meanwhile, there was Airbnb, born in 2008 out of a need for its founders to make rent by hosting strangers in their San Francisco apartment. But Airbnb’s brilliance was in its simplicity. It didn’t buy buildings or rent apartments. It didn’t need to. Instead, Airbnb connected people, hosts with homes to share and travelers looking for unique places to stay. It was a marketplace, and a marketplace scales differently. No debt, no heavy infrastructure, just technology and trust.

By 2011, Airbnb had expanded to 13,000 cities, yet its growth felt more like a well-choreographed dance than a mad dash. Each market was carefully evaluated to ensure demand existed before any heavy investments were made. This was reminiscent of how Facebook launched one college at a time ensuring the demand was there ahead of time. Airbnb stayed light, leveraging data, customer feedback, and existing assets to scale without the burden of enormous overhead. By December 2020, Airbnb went public with a valuation soaring past $100 billion, a stark contrast to WeWork’s implosion just a year earlier.

One company grew and did it recklessly, throwing money at expansion, hoping scale would follow. The other scaled intentionally, leveraging what already existed and ensuring that growth could pay for itself. It’s a tale of two concepts - growth vs scale. While there is a time for growth, as we’ve seen with WeWork, it has a significant amount of risk, especially when it’s done with reckless abandon.

Today’s article is about growing vs scaling. It’s important to understand the difference and to be deliberate about which one your company is trying to achieve. Let’s start by defining each. Growth and scaling are terms often used interchangeably, but their meanings are fundamentally different. While both are measures of progress, they differ in how resources are used and the sustainability of the outcomes they produce.

Growth refers to an increase in output achieved by a proportional increase in input. For example, a company might grow by hiring more employees, opening new locations, or pouring money into advertising to capture a larger market share. The growth process is linear: more resources lead to more results. Imagine a bakery that wants to sell more cakes. It hires additional bakers, buys more ovens, and rents larger kitchen space. It may double its production capacity, but it also doubles its costs. Growth often comes with more revenue, but also with more overhead, creating the potential for resource strain if costs outpace income.

Scaling, on the other hand, is a measure of efficiency. It’s about achieving disproportionate gains, where output increases without a corresponding rise in input costs. Scaling focuses on optimizing systems, automating processes, and creating a model that can grow sustainably. Consider the same bakery, but instead of doubling its space and staff, it invests in a state-of-the-art oven that bakes cakes twice as fast with the same labor and energy costs. The bakery now produces more without a significant increase in expenses. Scaling emphasizes doing more with less, leveraging technology, infrastructure, or innovation to expand capacity without proportional cost increases.

There are appropriate times for companies to grow and times for them to scale. Early-stage businesses, for example, often prioritize growth to establish a market presence, build their customer base, and gain traction. As companies mature, most shift their focus to scaling, optimizing operations and leveraging efficiencies to sustain expansion without straining resources.

Besides definitions, frameworks provide another way that we can build a common language for our teams. This lingua franca is important as it ensures that across our teams, when we use a term, such as growth, we all know what we are talking about instead of some of us misinterpreting that term. One framework that I’ve referenced before is Kent Beck’s 3X framework that provides three phases of maturity for products or companies – explore, expand, extract. Another framework that we used at AKF was people, process, and technology. I personally like this one as these three categories can be depicted as an overlapping venn diagram, because each of them impact the other. Additionally, visualize these are dials that can be turned up or down as the need exists. For example, if we do need to scale up via people, we might metaphorically “turn the people dial” in a myriad of ways including adding another layer of management in order to scale more efficiently instead of linearly.

Knowing when and how much to turn each of these scale “dials” is critical. Scale your processes too early, and you risk introducing bureaucracy that slows decision-making and innovation. Wait too long, and the organization can descend into chaos, unable to keep up with growing demands. Similarly, hiring people too quickly can inflate costs faster than revenue, while hiring too slowly may hurt customer experience and reduce quality. Technology follows the same delicate balance. Scaling infrastructure or automating processes prematurely wastes resources, while scaling too late jeopardizes efficiency and service. Success lies in finding the right timing for each lever, ensuring that people, processes, and technology grow in harmony with the business's needs.

There is no prescribed formula for how and when to turn each dial. This is indeed why scaling is an art. The good thing about scaling is that they are almost always two-way door decisions, ones that can be reversed, as opposed to one-way door decisions that cannot be. Besides understanding that these three categories of people, process, and technology need to be adjusted during scaling, the other common failure pattern that exists is not revisiting decisions on scaling. Once a company has decided to change a process to fix a scaling bottleneck, they almost never revisit that process/decision. A classic case of this is when a company does a build vs buy analysis for automating an internal process, such as keeping track of customer data, and decides there is nothing suitable and they should build it. A couple of years later and they are still supporting that internal tool and likely not adding features frequently enough for the team using it. What they don’t do is revisit that build vs buy decision. It’s likely that an entire industry has been built around that problem and there are lots of off the shelf solutions that would solve the problem better and cheaper.

Successful companies understand the difference between growing and scaling. They also make purposeful decisions about when to do each. Scaling requires ongoing vigilance. While initial decisions about people, processes, and technology are crucial, their effectiveness fades over time if left unchecked. Revisiting and refining those decisions ensures that what once solved a bottleneck doesn’t become one. The art of scaling lies in this dynamic balance of recognizing that the tools and strategies that brought a company to its current state may not be the ones that propel it forward. Successful scaling is not a single event but a continuous process of learning, adjusting, and optimizing.