I visited the United States Military Academy at West Point when I was about 13 years old. The visit wasn’t really special in terms of meeting anyone or getting a peek behind the gray stone walls into cadet life. Rather my family and I walked around on a self-guided tour, reading the various plaques and monuments. Mostly, I recall that after my visit I was completely enamored with the institution and the leaders that it has produced. My interest culminated with my application, nomination, acceptance, and attendance. I would say that marked the beginning of my leadership journey but like many young people, I was already developing my leadership skills in high school, whether I knew it or not at the time, through various other organizations, clubs, and sports. What it did mark was a much more formal and rigorous program focused on developing leaders.

Since that time, I have been a student of leadership. I don’t mean that in the formal, academic sense of studying leadership like some of my friends and colleagues but rather more from an ethnographic approach of observations and discussions. I have carefully watched excellent leaders in many situations, over many years, in order to understand what they do and how they behave. As part of that process, I have also spent some time thinking about how institutions, such as West Point, and the military in general produce leaders. Caveat that, of course, not everyone that graduates or trains in the military is a great leader, but the percentage of success is pretty high. Another caveat, as I mentioned above, I am not credentialed in this field. I am not an official spokesperson of West Point or the military. I have not even taught leadership in any formal setting. So, these are all just my observations.

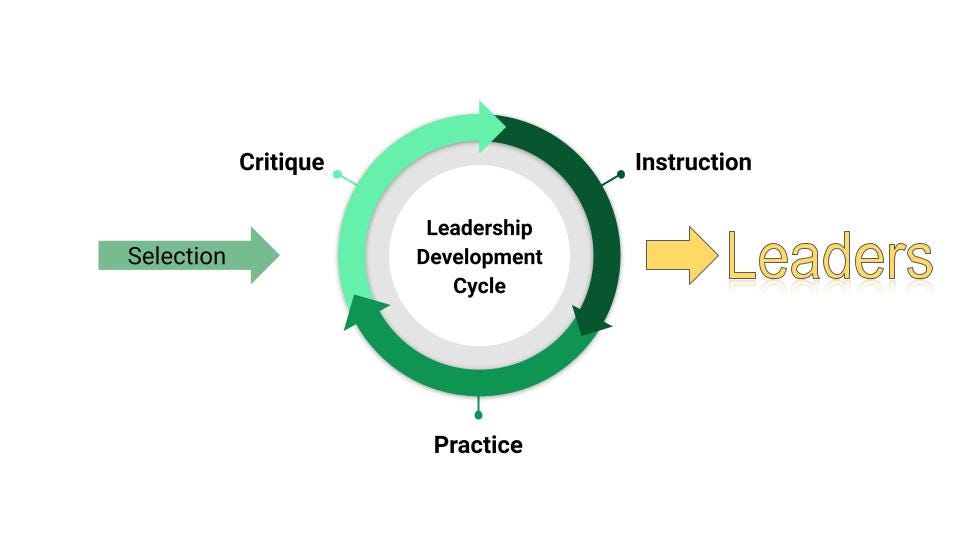

Looking back on all of this, what I deduced was that there appeared to be a three step process. The first step is selection. There is some minimum requirement for being selected to undergo training. For example, in order to join the military individuals must achieve a minimum score on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB), which is a test that assesses academic ability. In my experience, there is a very wide range of individuals who are capable of developing into great leaders. They come in all shapes and sizes as well as from all different backgrounds and even widely varying education levels.

The second step is instruction, often in a classroom, on the more theoretical aspects of leadership. This starts as early as basic training where newly enlisted soldiers are taught about followership, which is a vital part of leadership. Knowing how to be a good follower and getting the perspective of leadership from this vantage point is critical to one’s leadership development. While I’m calling this a distinct step, it is actually ongoing throughout a soldier's career through various courses that they attend as they increase in rank and tenure.

The final step is practice, practice, practice…with constant feedback. The third and final step is being placed in follower and leader positions constantly. If you need to move the team across the road…assign a leader. If you need to make sure the barracks are cleaned every morning…assign a leader. On and on, take every opportunity to allow people to practice leadership. And, the most important part is to have someone there, either an instructor or boss, who can provide feedback in near real-time. This often happens in an after action review (AAR) where the team sits down after some exercise and critiques how the team performed as well as key individuals. The purpose is constant learning and improvement.

Plenty of folks have been thinking about this process of leadership development probably long before President Jefferson signed legislation that established the United States Military Academy on March 16, 1802. In fact, ancient Greeks taught leadership through stories. One such example of this was Xenophon's book, Education of Cyrus, a partly fictional biography of the Persian King Cyrus the Great. While it appears to be a biography on the surface, it is in fact, a manual of leadership.

A much more modern version is the West Point Leader Development System (WPLDS). This is a comprehensive framework that integrates academic, military, physical, and moral-ethical development for cadets attending West Point. What I found most interesting is that the basics of the model (see diagram below) are indeed instructing the individual in physical, academic, military, and character programs and then practicing following and leading.

Source: WPLDS Model from Developing Leaders of Character

What I think is missing from this model and is the critical piece to developing leaders is the feedback from mentors, instructors, bosses, peers, etc. If you just practice following and leading without being told “you did this well” and “you did this not so well” you are never going to improve. Feedback is not just important but necessary in order to speed up the learning process. Without that, we are left to hopefully be insightful enough to decide what worked and what didn’t in various situations with different teams. With all of our biases and self-protective techniques, this is very difficult to accomplish.

Effective feedback is an essential catalyst in the process of developing leaders. It serves not just as a mechanism for improvement, but as a mirror reflecting both strengths and areas requiring attention, which is crucial for personal growth. Feedback in leadership development isn't merely about pointing out what is right or wrong but about creating a culture where open, constructive, and timely communication helps forge stronger leaders. This is particularly vital in institutions like West Point, where the stakes are high and the responsibilities vast.

The significance of feedback extends beyond correcting immediate errors; it fosters an environment of continuous learning and adaptability. Leaders who are accustomed to receiving and acting upon feedback tend to be more agile and responsive to the changing dynamics of leadership scenarios. They learn not only to accept critiques but to actively seek them out as opportunities for growth. This iterative process of action, feedback, and adjustment is what hones raw potential into capable leadership, ready to tackle complex challenges in military and civilian contexts alike.

While the WPLDS and similar frameworks document a solid foundation for leadership education through a structured mix of academic, physical, and ethical training, it is the integration of robust, ongoing feedback that, I believe, truly completes the leadership development cycle. Without it, the process risks producing leaders at a much slower pace and perhaps are lacking in critical areas because of their own personal blindspots. Therefore, embedding a culture of constructive feedback is not just beneficial but essential for cultivating leaders who are not only competent but also wise, reflective, and adaptable.

The cycle of performance and feedback is equally critical in the realms of product and engineering leadership, serving as a foundational element of effective performance management systems. For leaders in these fields, their primary responsibility may be to innovate and solve customer problems, but an equally significant task is the cultivation and mentorship of future leaders. Integrating a systematic feedback mechanism allows these leaders to continuously evaluate and enhance their team's approach to product development and engineering challenges. By fostering a culture where feedback is routinely exchanged, leaders not only accelerate the professional growth of their teams but also instill a practice of reflective leadership. This cycle ensures that emerging leaders are not only skilled in technical competencies but are also adept at critical thinking, problem-solving, and strategic decision-making, essential traits for leading complex projects and driving technological advancement.

Leaders must embrace the responsibility of developing their junior leaders as a priority, challenging them with opportunities that push their boundaries while providing insightful feedback that guides their growth. Encouraging this next generation of leaders not only strengthens your team but also ensures the sustainability and innovation of your organization, laying a solid foundation for future success.

Excellent as always. Effective feedback is so important. Interestingly, the only place I've ever received it has been in law firms. Maybe that's why I loved my time practicing law so much!!