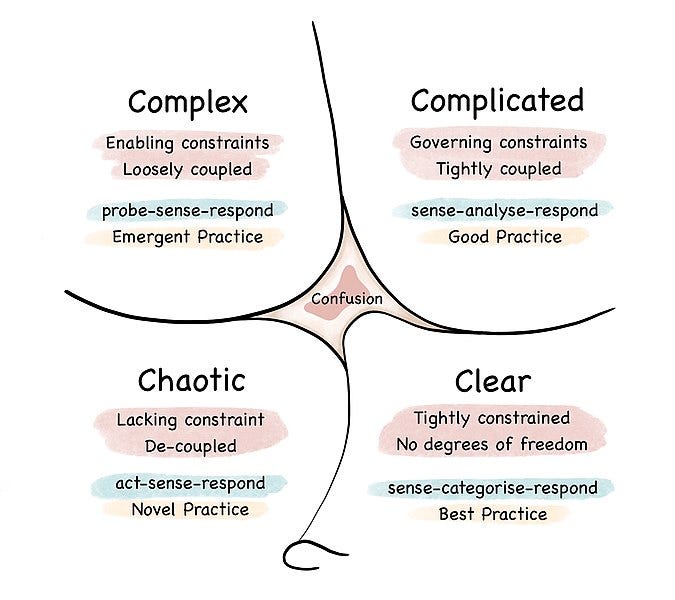

Some things are complicated, and others are complex. You'll recall from last week's post that complicated problems are difficult to solve but usually have a set of rules to follow. In contrast, complex problems have too many unknowns to reduce to a set of rules. But this is just part of the problem set. According to Dave Snowden's Cynefin framework, there are five contexts or "domains" that decision-makers have to deal with, including simple, complicated, complex, chaotic, and disorder. While this model was initially designed to help manage intellectual capital, it can be applied to various pursuits, including engineering teams.

Cynefin is a Welsh term referring to a "habitat" or "haunt." The term bears similarities to the Māori word "tūrangawaewae," which signifies a place to stand or the foundation and location rooted in your heritage and origins. Snowden employs this meaning to highlight the notion that we all possess foundations—tribal, religious, and geographical—that might not be apparent to us.

David Draper, Managing Director at Valtech, argues that the iterative approach of Agile teams is best suited for complex problems. This iterative approach becomes less effective when dealing with complicated problems that require more upfront analysis. He claims that developing a user interface is a complex problem, as there are so many unknowns. In contrast, the development of a technical integration is more complicated than complex. System APIs generally are well defined, and following a given set of rules is likely to lead to a desirable and predictable outcome.

The chaotic domain, in which cause and effect are unclear, is something that we, as engineers managing large, complex systems with major dependencies on third parties, sometimes find ourselves facing. Patrick Lambe writes that events in this domain are "too confusing to wait for a knowledge-based response...any action—is the first and only way to respond appropriately." The reason for this approach is that you are acting to establish order. Once this is accomplished, the problem can be framed in one of the other domains.

A situation I recently witnessed that reminded me of a chaotic problem was the SolarWinds hack. SolarWinds is a company whose products monitor, analyze, and optimize database performance. Most companies that use their products initially heard about the hack through unofficial channels, and they could not get a response from SolarWinds itself. One company I spoke with was unsure if they were impacted (ultimately, they found out they were not) but instead of waiting, they took action. They disabled the SolarWinds software and continued to monitor. Taking action put them into a complicated situation, as they had to monitor their databases differently, but it took them out of a chaotic situation where cause and effect were unclear.

Another example of how the Cynefin model was used occurred during a natural disaster. A company faced significant disruption to its supply chain and communication networks, making it difficult to assess the extent of the damage and what actions to take. By applying the Cynefin model, the company's leadership was able to identify the situation as chaotic and quickly move to take decisive action. They established an emergency response team and secured alternative suppliers to maintain operations. Once the immediate chaos was addressed, they transitioned to the complex domain, where they could develop a more in-depth understanding of the situation and make more informed decisions.

The Cynefin model can also be applied to management and leadership, helping to guide decision-making in various organizational scenarios. For example, imagine a manager faced with low employee morale and high turnover in their department. The manager could use the Cynefin framework to assess the situation, determine which domain the problem falls into, and develop an appropriate response strategy. In this case, the issue might be classified as a complex problem, as there are multiple contributing factors and no straightforward, one-size-fits-all solution.

To address this complex issue, the manager could employ an adaptive, experimental approach, involving employees in the decision-making process and testing various interventions to boost morale and retention. This might include initiatives such as flexible work arrangements, regular feedback sessions, or team-building activities. By closely monitoring the impact of these interventions and adjusting them as necessary, the manager can learn which approaches are most effective in their specific context. In doing so, the manager demonstrates the ability to adapt and respond to the complexities of their environment, ultimately leading to improved morale and a more engaged, motivated team. By applying the Cynefin model in this way, managers can enhance their leadership skills and better navigate the challenges they face in their organizations.

In conclusion, the Cynefin model is a valuable tool for sense-making in various situations. While it may not provide direct solutions, it helps decision-makers understand the context they are working within and guides them in developing appropriate processes and structures for problem-solving. By applying the Cynefin model, organizations and leaders can navigate the complexities of their environment, adapt to change, and make more informed decisions in the face of uncertainty.